Oh, this sodding book.

I…no, first, a little bit of context.

Those of us who call ourselves creatives, why do we create? Why do we have this need to make things? I know the usual answer is we write / paint / carve / whatever it is we do, because we have to, because there is something inside of us that needs to find an outlet. But what is that something? In my case, as well as a storyline it is frequently a place where I have spent some enjoyable time. It provides me with a comfortable setting in which to tell a story.

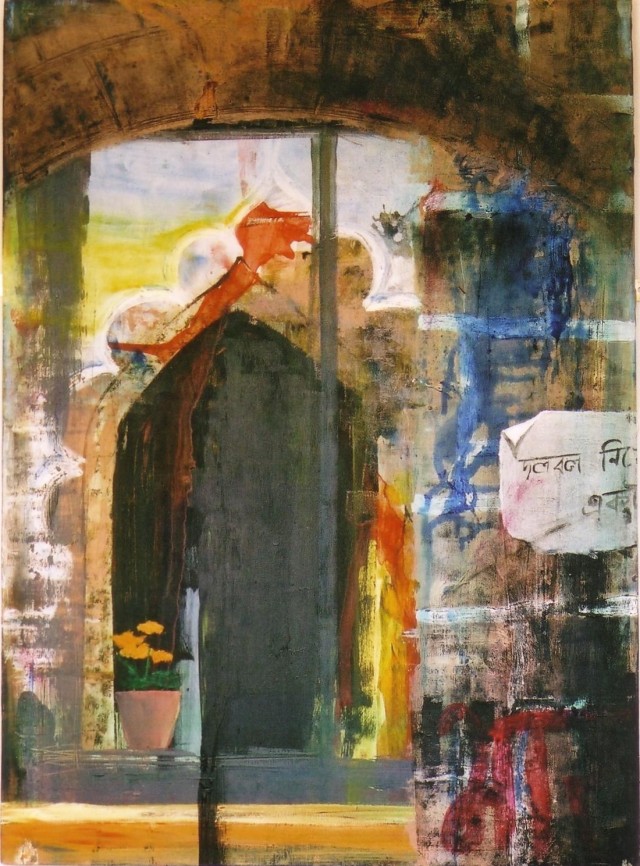

Most of what I do, certainly the work I feel is my best, my most successful (in the sense of expressing what I want to express), falls into that category. My long poem The Night Bus, for example, was the result of a thirty year (admittedly intermittent) search for a way to record my experience of a long bus ride across Northern India into Nepal. I attempted prose and paintings without success, although through this I did develop a style of painting I went on to successfully use on many Indian paintings, and had long given up on the project when chance showed me a way into the poem. The poem I completed succeeds in conjuring up (for me) the impressions and feelings I had on that journey; I can relive the journey again by re-reading the poem. Whether it conveys anything of that to other readers, I naturally cannot know.

And my stories, too. I look through Making Friends With The Crocodile, and I am in rural Northern India again. I re-read The Last Viking and can easily feel myself on an island off the west coast of Scotland. This is not to imply any intrinsic merit to my writing, other than its ability to transport myself, at least, into the setting I am attempting to describe.

These stories are a composite of three basics: a setting, as mentioned already, a storyline – and again this needs to be something important to me, or I find it pretty well impossible to put my heart into it, and strong, convincing, characters.

It is useful, then, to know where lots of my writing comes from, and what shapes it, what drives it. I have long suspected that this is frequently nostalgia and, recognising that, have wondered whether this might be a bad thing. Nostalgia, after all, has a rather bad press…does it just mean I am living in the past because I am viewing it through rose-tinted spectacles? As a way of not addressing issues of today I should be tackling?

This yearning for nostalgia, though, is a desire for something we see as better than what we have now. To write passionately about something it needs to be something I feel strongly about. Obviously this can also be something we find frightening or abhorrent – dystopian warnings about the future or anger about injustices, for example – but even in those cases the familiar provides a cornerstone of safety, even if only by way of comparison.

This is also true when I paint. I am not someone who can paint to order – if I’m not inspired, it does not work. A number of difficult commissions have proved that point to me. I paint what I like, what moves me. After all, whatever I am creating, it should be foremost for myself.

That book, then…

I began writing it about five years ago for all the wrong reasons. I had self-published Making Friends With The Crocodile and decided my next story should also be set in India, and as a contrast decided to write about British ex-pats living in a hill station in the foothills of the Himalaya. I wanted to write about India again. The trouble was, I had no idea what story I was going to tell. I had no stories that might slot into that setting I felt in any way driven to write; it just seemed to feel appropriate at the time. I was pleased by the reception the first book had and felt I ‘should’ write this one.

What could possibly go wrong?

I spent time putting together a plot, with which I was never wholly satisfied, and began writing. Really, I should have seen the obvious at that point and bailed out. But I carried on, and twice reached a point where I thought I had the final draft.

My beta reader then proceeded to point out all the very glaring faults.

So twice I ripped out a third of it and chucked it away, then re-plotted the second half of the book and got stuck into the re-write. I’m sure you can see part of the problem at this point – I wanted to hang onto as much of the story as I could, instead of just starting completely afresh. And now here I am trying to finish the final draft for the third time, as my February project for this year. And it’s just not working for me. But at this point, after well over a hundred and fifty thousand words (half of which I’ve discarded) I just feel I’ve invested too much time and effort in it to abandon it now. Somehow, it has to get finished. I do have an idea for a couple of quite drastic changes which I’ll try this week, but unless I feel I’m making some real progress I’ll then happily put it aside for a while and concentrate on next month’s project: painting and drawing.

And, to be honest, if it eventually ended up as a story of less than ten thousand words, and if I felt satisfied with it, then I’d take that as a result, now.

And the moral of all this? I’m sure there was a point after a couple of months when I knew I shouldn’t have been writing this book. I should have binned it there and then and saved myself a lot of fruitless trouble, but stubbornly ignored the warning signs.