The May Day festival, Beltane, is a survival, or revival, from the Iron Age, celebrated in Celtic communities – Scotland and Ireland particularly – and revived as a full festival in Scotland in the 1980’s by the Beltane Fire Society. Beltane was a fire festival, although nothing of that remains in the festivities carried out in England. Beltane was first mentioned by name in Irish writings from the late 800’s / early 900’s.

The English version of this festival involves cutting flowers and greenery and dancing around a maypole, which things are also carried out during Beltane, celebrating the beginning of Summer which begins on May 1st. When I was a child, dancing around the maypole was the chief, possibly only, activity carried out on May Day. I have a photograph of my brother, my cousin, and myself, dressed up for the May Day Fair at which there was maypole dancing, but no obvious indication of surplus greenery. Past generations in England celebrated May Day with a day of celebrations which while including maypole dancing as an important manifestation of encouraging the fertility of the soil (and the festival-goers!) would also have included plenty of food and drink and general gaiety.

Mayhem, if you like.

This year, I managed two May Day days out.

On Saturday, two days before May Day, I visited Kingston near Lewes, in Sussex, for the Caught by the River Mayday event. Caught by the River describe themselves as an arts/nature/culture clash and you can read all about them here. I have followed them now for several years, and this seems as good a time as any to mention that their coverage of arts, nature, and culture are second to none and if you’re not yet following them, well, you should be.

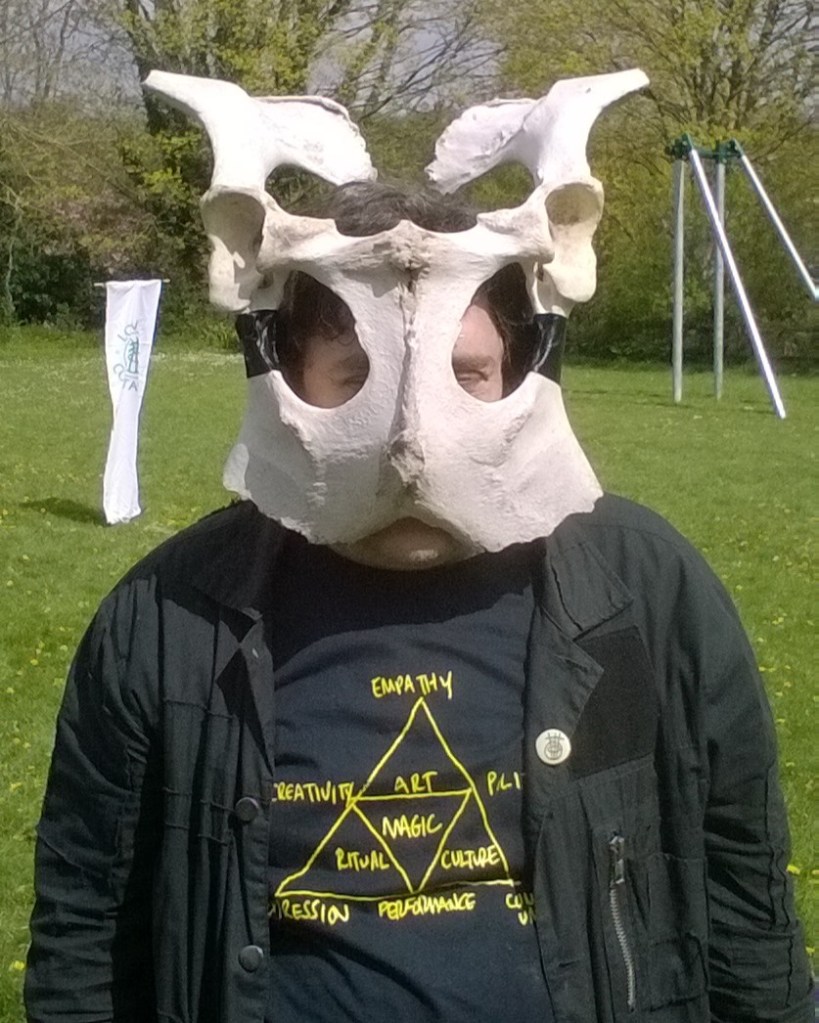

There was mask-making to begin with, especially to involve the children, the makers encouraged to incorporate flowers and greenery into their masks, and almost inevitably a certain amount of folk-horror found its way into some of these.

Nice, Richard.

This was followed by a promenade around the maypole, after which the activity moved indoors.

There were films, talks, and discussions, subjects including rivers, village life in the early eighteenth century, art, standing stones and the like, and the environment. After which, in the late afternoon, we all promenaded up the hillside to the Gurdy Stone.

This is the Gurdy Stone, a modern standing stone on a hillside overlooking Kingston. Here, Local Psycho (Jem Finer and Jimmy Cauty), held a gathering to encode the music of their Hurdy Gurdy song into the stone “To mark the 50,000 year return of the Green Comet and release of The Hurdy-Gurdy song on Heavenly Recordings.”

Throughout the day, naturally, we all had access to the pub.

And then on Monday, which was May Day, we went down to Hastings. It rather felt as though everyone in South East England must be in the town, either at the Jack in the Green festivities or watching blokes on motorbikes roaring up and down the seafront for no discernible reason. I don’t much like crowds, and some of this was very difficult. But away from the huge horsepower and testosterone nonsense, amongst the Jack in the Green celebrations the atmosphere was brilliant and the large numbers of people perfectly acceptable. Jack in the Green is a manifestation of the spirit of spring, related to the Green Man, a dancing figure covered in greenery.

The festival in Hastings has grown over the years into a large event involving musicians, dancers, Morris sides, huge figures in addition to Jack in the Green such as the Queen of the May, a witch, and others, plus any number of people joining in the procession around the town, all decorated with as much, or as little, greenery and/or flowers as they feel suitable.

There you go, a Morris side.

Followed by a large witch with a cat. Why the witch? I’ve no idea. Why not? I suppose.

And there you have it. Music. Drumming. Greenery. Crowd involvement. Summer is icumen in and winter’s gone away-o.

And there was beer again, of course.