A few days ago we went to the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne, Sussex, specifically to see the Eric Ravilious paintings and prints on permanent exhibition there. There was also a large exhibition by the sculptor David Nash, who works with wood on a large scale. The fact that the whole exhibition, which also included a gallery of paintings, prints and a couple of small installations, and was intended to highlight the effects of the Climate Crisis, was the first one ever curated by Caroline Lucas M.P. of the Green Party was an added bonus for me.

As much as I enjoyed the Ravilious, I was blown away by Nash’s sculptures. To see wooden sculptures on that scale is unusual in itself – usually that would be the preserve of stone or metal – but that very scale plays tricks with the mind and the eye. Boxes and bowls many times larger than one would expect meet the eye as you walk around the galleries, and many of the pieces also deceive where perhaps one looks to be made from several separate pieces of wood, but on closer inspection are carved from a single block like the boat shapes in the top picture, or the ‘stack’ in the one below that.

Much of the work is left rough-hewn, but even this can be deceptive. Some pieces have been carefully finished to give that appearance.

Sculpture is the art form that seems to exist to interact with the natural world. A number of the works here are based on natural forms, but there are also stories of projects Nash has undertaken where his sculpture is either living, in the form of carefully planted and managed groves of trees, or interact in other ways.

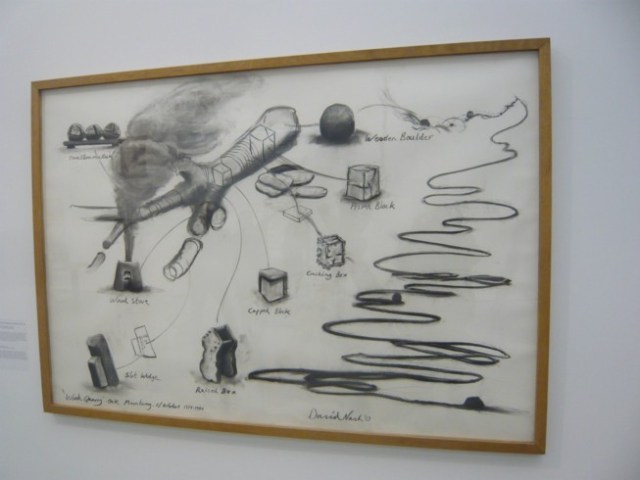

‘Boulder’ is one such project. One of the first large-scale pieces Nash made was to cut a boulder-shaped chunk from a tree (illustrated at the top of Nash’s charcoal drawing above) in 1978. This was then transported to a stream near to where he lives and works, in the Welsh hills, and rolled into the water. Since then, it has slowly made its way downstream until it reached the estuaries and inlets of the sea, where it finally disappeared in 2015. Nash documented its travels in a series of photographs and films made regularly all the while, and presented in the exhibition as a film.

Nash’s sketch of a Larch trunk

It feels as though there is something of this meeting of art and the natural world in old ruins overrun with scrub and grass. They frequently seem to have a sculptural quality that complements the landscape around them, in a way that more pristine buildings do not.

And I like the sense that an artwork, like a ruined building, is not permanent and that eventually the natural world will absorb it back into itself. That it will reclaim it. Perhaps the artist and the environmentalist in me merge here.

My own sculptures are in wood, and some of them are set out in our garden where they gradually degrade over the years through the action of sun and rain, until they appear strangely like some weird plants that have sprouted unexpectedly there.