When I lived in Oman, the land around where I lived and worked was all stone desert; hills and valleys of razor sharp broken boulders, water worn stones at the bottom of dry valleys, with occasional villages and settlements and old, crumbling, mud brick forts dating from the time that the Portuguese were there. Almost invisible tracks used by goats and nomads wound their way through this wonderful landscape, or simply followed the routes of the wadis, the dry river valleys. I had a very small scale map of the country, as well as a few very large scale maps that I had pinched from the office where I worked (I did return them when I left). These would consist largely of huge areas of blank paper, with the occasional ‘tree’ or ‘large boulder’ helpfully marked, although they did show the main wadi courses and mountain ridges.

I was very tempted to write ‘here be dragons’ on them occasionally.

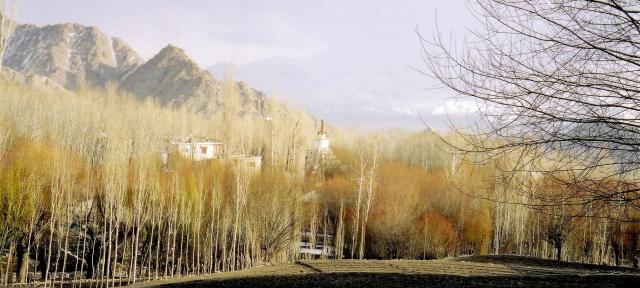

Never before had I quite understood what silence was. And it was the first place (to be followed by the Himalaya) that I was to truly see a night sky. I was periodically astonished by the desert’s outbursts – blasts of hot wind like an opened oven door; flash floods that appeared from a blue sky in minutes, to ferociously drench the unfortunate climbers on the top of a previously baking jebel (hill); and tiny earthquakes and landslides – I was no doubt fortunate never to witness a serious one. I would overnight in the desert with friends and we would lie on our backs to watch the unbelievable night sky with its thousands of stars, satellites and shooting stars, before ascending a 10,000ft mountain in the morning, or exploring a stretch of uninhabited coastline.

I spent almost every spare hour that I had out in that desert, either trying to find my way across trackless ridges in my jeep, or just walking; walking everywhere within walking distance and discovering just how much there is actually to see in a desert. I was supremely happy in that environment, and some 20 years later when I had to change aircraft in Muscat, I found myself looking out at the purple tinted hazy mountain lines with something very close to homesickness.

Today, even waiting on the station to get a train to go to the next stop, a coffee in hand, a bag over my shoulder with a book in it, I am on a journey. And that journey feels clearly related to the longest journeys that I have ever taken. There can still be the same sense of travelling, of departing and arriving. The search for food and shelter… I think that it shows just how much a journey largely exists in the mind. Often our perceptions of a journey seem to differ from that journey’s reality (as many things do, I suppose). A long, difficult journey can seem to be over quicker than a short, easy one.

Just packing a rucksack, even an overnight bag when I used to have to occasionally stay over where I once worked – a wash bag and towel, sleeping bag and clothes – I feel as though I’m off on a journey. There is a certain amount of excitement…

And I know, too, how smell is such a strong, evocative, sense. Just with the kitchen window open, at 10pm on a slightly rainy October evening, I suddenly catch a scent of something – something cooking nearby, or a hint of smoke, perhaps – and I am instantly transported to Nepal, high in the mountains, remembering an evening with sherpas and villagers beside a river where we ate and then sat around talking and drinking and listening to those sherpas and villagers singing.

Okay, I’m ready to go and pack, now…