More people travel for leisure purposes today than have ever done so in the past. And many work abroad on short- or long-term contracts, often with a certain amount of leisure time available to experience the culture that surrounds them there.

And this will result in these travellers meeting the people that make up the indigenous society where, for a while, they find themselves. Will there then be a meeting of minds?

Having lived in an ex-pat society, as I have referred to on here before, I am familiar with the laager mentality that often pervades it. I won’t go into all the permutations, but there is frequently a combination of arrogance and fear that leads to a strong feeling of ‘us and them’.

Many travel with the firm conviction that their own society is superior to any other, and are unwilling to see any good at all in any others. Some who go away to work resent being uprooted, and arrive with that resentment packed in their baggage. Some find the experience to be fearful, if they do not understand the language being spoken around them or assume that this alien society has values that somehow threaten them.

And they can either lock themselves away and peer over the barricades, or they can embrace the experience and learn from it.

Travel broadens the mind, it is said, but sometimes it seems to just cement prejudices more firmly in place.

And how easy it is to travel around just looking for things to justify prejudices!

One of the more infuriating things that I come across occasionally is a bigoted and ignorant letter or article in a local newspaper (it often tends to be the local ones) where someone’s idiot views are justified by the phrase ‘I know; I was there’. I imagine them living their entire time in a foreign country in a compound that they rarely leave, yet thinking that they now know exactly how the society functions beyond their walls.

I’ve met one or two of them, over the years.

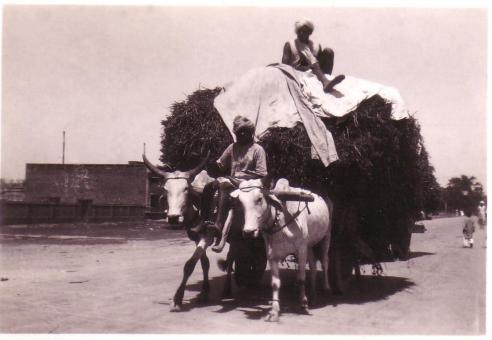

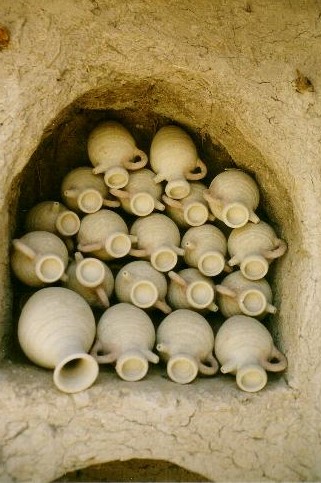

I spent three years in Oman, working, and I’ve travelled fairly extensively in India, but I do not imagine or pretend that I really have much more than a superficial experience of these places. I knew little of the local culture in Oman beyond what I could see in the streets and villages and markets that I visited. I didn’t know anyone well enough to spend time at their homes or in their social circles. I went with groups of other westerners to places of interest. I did spend a lot of time exploring the desert and the nearby towns on my own, but I was effectively still inside my own little bubble. It is a huge regret that I never got deeper under the surface.

I have, perhaps, managed to learn a little more about the real India, especially through spending time on a project in a village, although I cannot pretend, even to myself, that I really have any idea of what it is like to actually live in an Indian village.

During the later days of the British Raj, the rulers took the approach that their civilisation was naturally superior, and that there was nothing in Indian civilisation worthy of their consideration. The irony of this is that around the end of the eighteenth century, and the first years of the nineteenth, many of the British in India had taken a keen interest in Indian history and culture, themselves doing a tremendous amount to unearth much of the history that had been lost and forgotten. For that comparatively brief period, it would seem that many of the British treated Indians and their culture with a deep respect.

The reasons that this changed are probably deeper than my understanding, but two things stand out. Firstly, that from the beginning of the nineteenth century, many British women came to India in search of husbands, bringing with them what we tend to think of as Victorian attitudes, and secondly, there was an upsurge of evangelism in Britain, which translated itself in India as a movement to convert the ‘heathens’ to Christianity. These combined as a new feeling of superiority, and contempt for a society that was now seen as inferior, especially when much of it resisted their overtures.

With this, the British as a whole seemed to become more intolerant and arrogant, and less respectful of sensibilities. This culminated in the horrors of 1857, which could be said to be caused directly by these attitudes.

To return to the present day, it seems that many travellers have attitudes no better than their Victorian predecessors’. I wrote a post a few months back that mentioned a number of westerners I came across in a Himalayan hill resort, https://mickcanning.co/2015/10/25/the-mad-woman-of-the-hill-station/ should you wish to view it, whose behaviour and attitudes were just downright arrogant and disrespectful. They were doing no more than confirming their prejudices as they travelled, and at the same time I daresay they were confirming many people’s views of western travellers.

Yet there are many people who travel with open ears, open eyes and an open mind, and their rewards are far greater than those of the blinkered traveller. They have the wonderful opportunity to experience and learn about different cultures at first hand, speak to people who hold different beliefs and ideals to them, and perhaps learn a little of what drives them. In return, they have an opportunity to enlighten others, perhaps, to things in their own society that might not be understood by those others. In a small way, each and every one of them can choose to contribute either to different societies coming to understand and become more tolerant, or to the further spread of tensions, mistrust, and misunderstandings.

And all of these little interactions, added together, are as important and influential as the contacts between politicians and diplomats.