18th June 1994

My coach got into Inverness at 8.10pm after almost twelve hours on the road, and I was more than ready to begin walking. With over two hours of daylight left, I aimed to get well clear of the city and find a good spot to camp for the night. I grabbed a bag of chips from a chippy, then followed the Caledonian Canal southwest for about four miles, left it and climbed a little more to the west to find somewhere to sleep. I filled my water bottle from a stream, then wandered into a little wood and got out my bivvi tent and settled down for the night, black clouds heading slowly towards me as I did so.

19th June 1994

This morning is dry and bright, but quite windy. I boiled some water for coffee and set off as soon as I could, intending to make the most of the good weather. Today I intend to cover quite a few miles on side roads which I hope will be carrying very little traffic and so get a substantial fraction of the journey under my belt before the weather gets any worse. This is Scotland, after all. I‘m expecting rain. It should also break me in gently, being easier ground than much I expect to have to walk. So, I’m aiming for Urquhart Castle, which overlooks Loch Ness and will be a slight diversion from my route but I just fancy having a look at it, and from there I can leave the road and follow the river southwest through Glen Coiltie before turning further towards the west.

As soon as I set off, I was walking straight into the teeth of a strong wind. Long distance footpaths are usually walked from west to east, at least in Britain, and there is a strong argument for that; we get the majority of our weather from the west, so by doing that we have the wind (and whatever it brings with it) at our backs. I’m walking it in the opposite direction not just because I am naturally perverse – or not only for that reason, anyway – but because the more interesting and exciting scenery will be on the west side of the country, and hence my destination. Walking from west to east I feel I would arrive at my destination with a certain amount of disappointment, with all due respect to Inverness which is a delightful city, but I’m after the spectacular wilderness.

So, into the teeth of a strong wind. It is not long, though, before I am walking through Abriachen Forest and I stop for a rest sheltered from the wind.

I rather think Abriachen Forest has changed a little since I passed through there in 1994. I remember it as a dark wood of densely planted conifers, typical of the conifer woodlands planted in the middle to late twentieth century with the intention of producing the maximum possible yield of wood. The trees allow so little light through that other than the trees themselves – Douglas Fir and Sitka Spruce, typically – these plantations (forest is the wrong word) house very little life. But in 1998 the community of Abriachen (a small village) purchased 540 hectares of the woodland and since then have been improving it – thinning the trees, reintroducing native species and creating footpaths and trails.

But on the edge of the forest, and beside the road, there are a multitude of flowers: vetches, Ladies smock, and violets, particularly catch my eye. I draw away from the forest and I am back amongst a more natural landscape, with banks of pepperminty smelling gorse, occasional rowan trees in blossom and heather beginning to flower.

Now, for the first time, as I leave the road and walk uphill along a track towards the farm of Achpopuli, I get my first good view of large snow-covered mountains to he west. Once past the farm, I am on a supposed footpath heading up towards a saddle between two hill crests but the ground is extremely boggy and proves to be a taste of much of the rest of the route. My feet sink about six inches into either water or soft moss and heather, slowing my progress significantly. But then I m over, and down to a small loch where I stop to refill my water bottle and have a wash. I am surprised by how warm the water is, and I brave a quick dip as well as a shave.

On, then, to Urquhart Castle and then a little further out of my way to visit Divach falls, a waterfall with a drop of about a hundred feet. And near the bottom, primroses were still out.

Following a track up Glen Coiltie looking for a suitable spot to make my camp and cook supper I am walking through old forest, such a contrast to the plantation I walked through earlier. The trees are so covered in mosses and lichen it seems at times almost a wonder they are still alive. The path winds up and down and left and right and feels at times like a high mountain trail. Far below I hear the roar of the river, and for almost the first time that day feel I am absolutely in my element.

Eventually I make camp in a small hollow just below Carn a Bhainne. There is a low ridge towards the west which should shelter me from the worst of the wind. After I have eaten, I sit with a mug of tea looking across the river towards a snow pocket that is probably a couple of hundred meters higher than where I am.

found stag beetles and slow-worms, caught minnows and sticklebacks, and absorbed a lot of knowledge about trees and birds and insects and mammals from books and TV programs and just being out in the country.

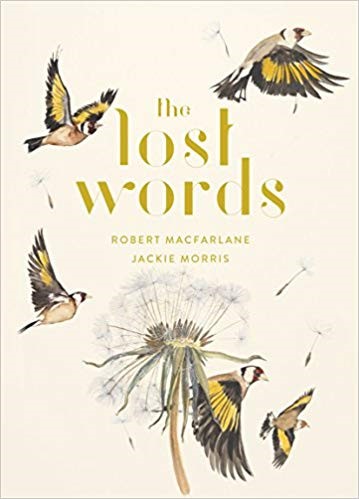

found stag beetles and slow-worms, caught minnows and sticklebacks, and absorbed a lot of knowledge about trees and birds and insects and mammals from books and TV programs and just being out in the country. and kingfisher and acorn are words that the majority of children today are unfamiliar with – something that would once have been unthinkable. And this disconnect seems to me the saddest thing. So much of our very rich heritage has a rural background, be it music or literature, architecture, leisure activities, or traditional crafts. And the same is naturally true for most countries and societies.

and kingfisher and acorn are words that the majority of children today are unfamiliar with – something that would once have been unthinkable. And this disconnect seems to me the saddest thing. So much of our very rich heritage has a rural background, be it music or literature, architecture, leisure activities, or traditional crafts. And the same is naturally true for most countries and societies.