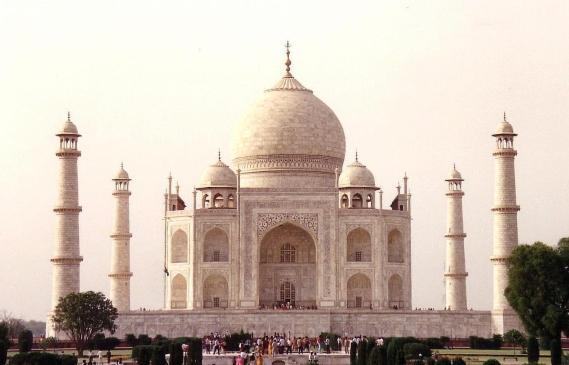

Fifteen years after my first trip to India, I was back again in Delhi.

On the first morning I had breakfast, and then had a bit of a walk around being hassled. It proved very difficult, as an obvious westerner, to walk around on my own. One or two beggars approached me, although they were neither numerous, nor persistent, at this point. The strangers offering ‘good advice’ made me more circumspect. They may have been simply being helpful, or they may have been touts. I was advised to go to a nearby ‘Tourist Office’ or ‘Travel Bureau’ – usually a private enterprise in India – for maps and information on what to see. I was advised to carry my bag differently to thwart thieves – no doubt kindly meant. Every step that I took deeper into Paharganj I was accompanied by one or two chaps unobtrusively wandering along at my side, until I began to feel that I had had enough of it. A number of people were out to sell me things – anything from hashish to bus tickets. In the end I dived into a café for a cup of tea to give myself some space and to formulate a strategy for dealing with all this. I was, after all, going to be in India for another three months.

Yes, three months. How came this to pass? The reason was simply that I had become pretty fed up with all of my routines in England. I might say that I was bored; I might say that I felt as though I was stuck in a rut. I might also say that I had come to loathe the work that I was doing. Clearly, some sort of change was required, even if only a temporary one so that I might feel refreshed. Sitting in a pub garden in the sunshine, in a village a few miles from where I lived, drinking a pint of Mr Harvey’s splendid ale, I decided that I would walk around the U.K. As you do. The fact that I now clearly wasn’t walking around the U.K. may require further explanation.

I spent some months working out an itinerary; poring over maps and drawing felt tip lines here and there on them, reading up on places I had never been to, and reading accounts of people who had done this sort of thing before. After rejecting a coastal walk (I’m not mad keen on the coast; I prefer hills and mountains and woods and really don’t like seaside towns) I eventually decided upon a rough route linking up long distance paths and places of interest that ran haphazardly around the island, and decided that I was permitted to take buses and trains to avoid cities and the suchlike. Friends I spoke to said they’d accompany me along the way for a few days here and there, so I didn’t have to put up with my own company all of the time (they generously offered to put up with it instead). I estimated that the project would take four or five months.

I got quite excited about it. And then I decided to walk Offa’s Dyke Footpath (which very roughly follows the border between England and Wales) as a sort of training run (well, walk), and things rapidly began to go wrong.

I couldn’t believe how much stuff I’d crammed into my rucksack. This certainly wasn’t the first time that I had gone long distance walking; carrying everything that I needed to camp along the way, but it seemed that I had about twice as much stuff as I’d ever taken before. How on earth had that happened? I crammed and jammed the last of it in and forced the zips closed. Then I tried to lift the thing; it was ridiculously heavy. I unpacked it and discarded clothes, until I felt that I really had the bare minimum necessary. I got rid of one of my two cooking pans. One of my two books. One or two other odds and ends were jettisoned. I could shut the bag a bit more easily, now, but it still weighed a ton. Should I chuck out the tent and just take a bivvy bag? In the end I didn’t, since it was a lightweight tent that was only fractionally heavier and bulkier than the bivvy bag would have been. Did I really need to take photos? Did I really need to wash? I was still dithering when the time came to leave the house and catch my bus.

The following day I walked out of Chepstow on the first leg of the footpath, with what still seemed like half a ton of stuff on my back. I kept thinking that I’d be carrying even more with me for the four or five months that it was going to take me to do the real thing. But the first day went okay, and I reached the place that I had decided to spend the night after a very pleasant walk. It was the next day that I first twisted my ankle. I’ve always been a bit prone to this; it seems that my left ankle has some sort of weakness, which is probably the legacy of an older injury.

I went down in agony. Eventually the pain subsided enough for me to get carefully to my feet, get my rucksack back on and hobble painfully on my way. It took some while, but after perhaps an hour or two, I was moving fairly well again. Then, towards the end of the afternoon, I began to walk down a hillside towards my campsite, when my foot twisted under me and I went down again with a great yelp of pain and a torrent of bad language.

After that, things just went from bad to worse.

The following day I cut myself a strong walking stick from a wild briar, just outside of Monmouth. But even so, I twisted my ankle a further two or three times that day. The scenery became lovelier and lovelier, but I only had eyes for wherever I was next going to place my foot.

All the joy had gone out of the trip.

On day four, I managed to walk through the best scenery so far without further mishap, and then walked the last few hundred yards into Hay on Wye where, you guessed it, I twisted my ankle. I stayed two nights in Hay, enjoying the bookshops but especially enjoying not carrying my bag around, and the next day I took a bus home, defeated.

I still needed a journey, though, and after a while I thought of India. I had spent a couple of weeks out there some fifteen year’s previously, and had yearned to return and explore it further. And so I began to draw up a new itinerary.