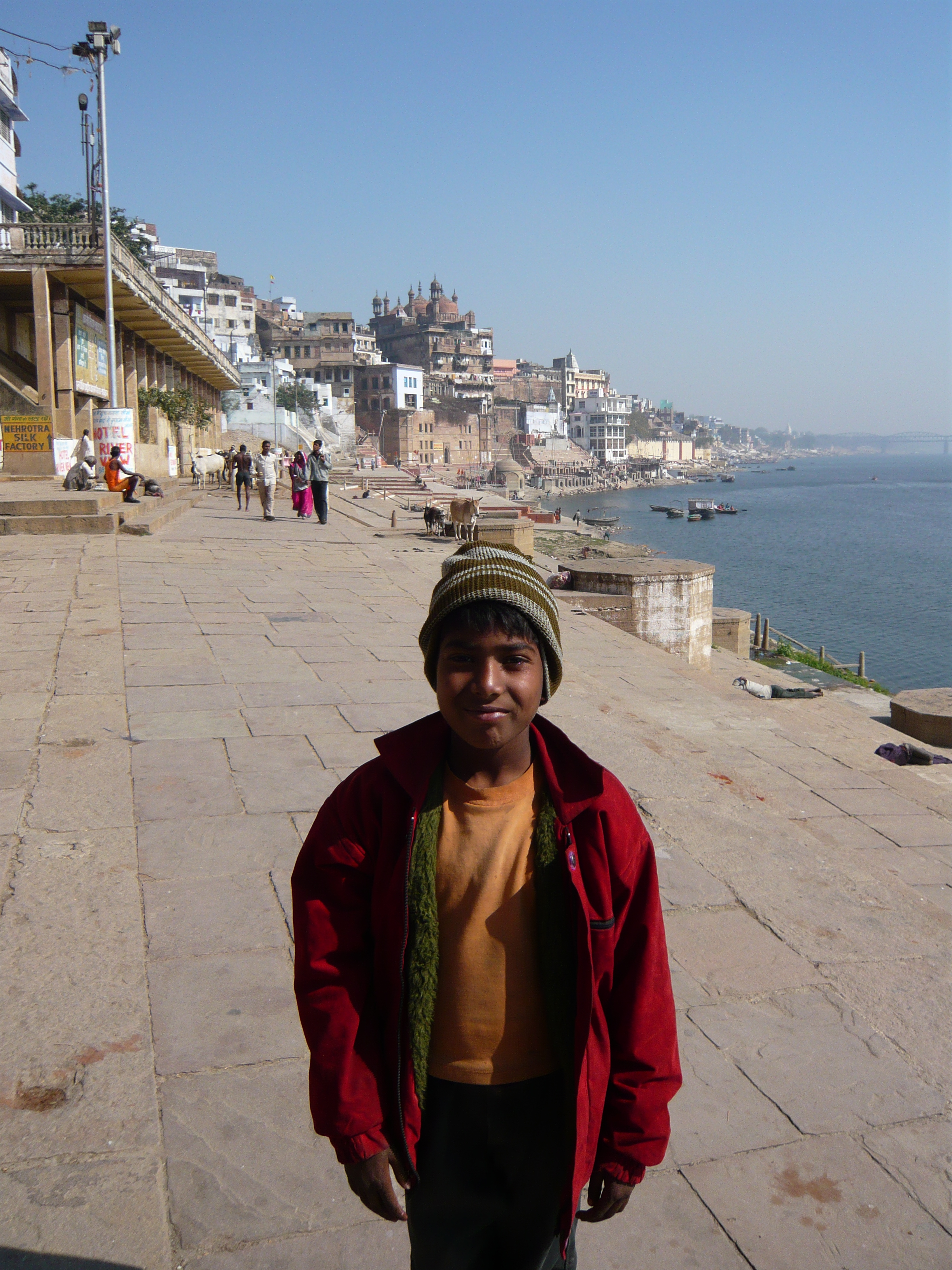

Although not perhaps the first county one would think of when discussing ancient standing stones, Kent does have its share. There are two main sites approximately equidistant on either side of the river Medway in north Kent. The eastern site consists of the remains of two burial chambers (Kit’s Coty House and Little Kit’s Coty House) and the White Horse Stone, all within a kilometre of each other, while the western site consists of the Coldrum Stones (burial chamber) and Addington Long Barrow and Addington Burial Chamber.

The Coldrum Stones

At Little Kit’s Coty House in a light drizzle, I counted seventeen stones, although Donald Maxwell writing in The Pilgrim’s Way in Kent, a short guide published in 1932, claims twelve to fourteen. Various other authorities suggest between nineteen and twenty-one. This is one of those sets of remains that comprise such a jumble of stones it is supposedly impossible to accurately count them – and just to make it harder, they are also supposed to move around (presumably when no one is looking). Thus they are also known by the name The Countless Stones. The largest ones I reckoned were about four meters by two and about three and a half meters by three. The shapes are very irregular, and since they are in a collapsed state there might have been serious damage to some of them. I immediately wondered whether it had originally been the same shape as Kit’s Coty House, a Neolithic chambered long barrow, just a few hundred meters to the north, where the stones are in the form of a dolmen, which would have been a burial chamber at one end of an eighty-four meter mound.

The Countless Stones, or Little Kit’s Coty House

William Stukeley, writing in 1722, recorded that he was told local people remembered a chamber at Little Kit’s Coty House. It had had a covering stone and was pulled down in about 1690.

Both Kit’s Coty House and Little Kit’s Coty House are reckoned to be just under six thousand years old.

Kit’s Coty House

Some nine or ten kilometres away across the Medway Valley are the Coldrum Stones, or Coldrum Long Barrow, dated to between 3985 and 3855 BC. These ones, looked after by the National Trust, are also a burial chamber. Donald Maxwell claimed that there were forty-one stones and that a further fifteen were broken up at an unspecified date during quarrying work. Maxwell also reported a tradition ‘amongst the country people’ that an avenue of stones stretched across the valley from Coldrum to Kit’s Coty, although there is no evidence it ever existed. But coincidence or not, both of these chambers are situated at the same height, about eighty five meters above sea level.

All three burial chambers, then, have been dated to the same period, a thousand years before Stonehenge was built. It seems reasonable, then, to assume they were produced by the same society.

Coldrum has been proved to be a family tomb, the remains of at least 22 people being interred there, with DNA analysis proving their likely close family relationship. Yet amongst these kinsfolk, recent isotopic analysis has shown that maybe the chamber also contained the remains of individuals interred in the fifth to seventh centuries AD.

The White Horse Stone

I say maybe, as there is a very strong caveat connected to this research, and that is that when the human remains were removed in the early twentieth century they were not only not labelled very thoroughly, but they were also passed around several museums and the possibility exists that some bones ended up mis-accredited. Yet it has been proven that some neolithic burial chambers were re-used for burials in the early Anglo-Saxon period.*

The land here has been sculpted by man. Of course, we sculpt the land more and more violently and obviously in the twenty first century, but here, from all these thousands of years ago, are these simple shapes built by ancient folk to inter and celebrate their dead. And these were interactive places. Evidence from other sites shows that some of the bones of these ancestors would be removed at times, although whether as a simple reminder of their elders, or whether for magic or sacred purposes, can only be conjecture. But I like the thought that these bones might be invested with power, that they could be brought into the everyday for protective or ritual purpose.

Now, we view them in a different light, and their sacredness has evaporated. Like a deconsecrated church, but without ever having been formally deconsecrated. It is possible our ancestors would view our visits there as desecration.

But I’m never sure whether you can take any arrangement of stones for granted; they’ve been dismantled in the past, could they have been reassembled?

Incidentally, for those who enjoy Ley Lines, it is worth mentioning that the Ley Line hunter Paul Devereux has described a line passing through The Coldrum Stones and aligning with six nearby churches. Although just to put a dampener on that, perhaps it is also worth mentioning that students at Cambridge University investigated this particular line using computer simulations based on the Ordnance Survey details and concluded that it wasn’t statistically significant – that it was almost certainly just a chance alignment. You takes your pick.

*Research carried out by members of Durham University, Oxford University School of Archaeology and British Geological Survey (Isotope Facility) 2022