The second and final part of an early travel post:

A few more photographs from 1989 (my apologies for the quality of some of them – all I had with me was a very cheap camera):

After a few days in Delhi, I went to Srinagar, in Kashmir. I took the bus that went through Jammu, and 24 hours after leaving I was deposited in Srinagar.

On the way, I did one of the most stupid things I have ever done in India.

The bus was packed. I think that I was the only westerner on the bus, but I liked it that way. On a 24 hour bus trip, it is pretty well impossible to ignore your neighbours for the entire journey, and so I spent much of the time chatting with the chap sitting next to me, and the ones across the aisle. When the bus halted to allow us to get some food, we sat at the side of the road together munching on the samosas, pakoras and newspaper twists full of nuts that we had bought.

When it started up again, we chatted long into the night before falling asleep.

And at the first stop just after dawn, at another cluster of roadside stalls for breakfast, I joined them at the broken water pipe beside the road where we all brushed our teeth.

Maybe if I had spent longer than just a few days in India by then, the consequences would not have been so violent. But as it was, my stomach had clearly not yet adjusted to Indian bacteria.

And maybe if I had spent longer in India I would have realised that it was not a clever thing to do in the first place.

In Srinagar, I stayed on a houseboat on Lake Dal. I no longer remember what it was called, but I was the only guest, and I had the place to myself. These wonderful floating mini-palaces are a relic of the days of British India, when the local Prince refused to allow the British to purchase land to build houses. They got around this by causing the construction of houseboats to stay on, instead. Made from wood, beautifully carved, and furnished opulently throughout, they seemed to me to be unspeakable luxury after my 24 hour bus journey.

The rapidly multiplying bacteria in my stomach, though, were clearly in a hurry to join all of their friends in the Lake. But for someone feeling poorly and reluctant to stray too far from a bathroom for a few days, the houseboat could not have been better. I had my meals cooked for me, and any little treats I fancied I could buy from one of the many shikaras that continually paddled up to the houseboat. These little boats, which also acted as water taxis, sold chocolate, flowers, fruit and vegetables, cigarettes, snacks, flowers, newspapers and yet more flowers.

I passed much of that time on the deck or on the roof reading, or chatting with the folks around me on the nearby boats or on the shikaras.

After a few days I recovered enough to explore the area a little. I walked many of the paths around the lake, which is a more complex shape than the visitor first realises. I would frequently find myself on causeways or small spurs of land sticking far out into the lake. I wandered around the Shalimar and Nishat gardens, and I walked up the long, winding path to the Shankaracharya Temple, on the hill of the same name.

This was March, 1989, and even someone as unobservant as me could not fail to spot the signs of unrest. Once or twice in the evenings I heard what might be shots or small explosions in the distance, which my host casually dismissed as ‘bandits’. On one occasion, walking through Srinagar I found the road blocked outside a mosque, where there was lots of shouting and a large police presence; although on reflection, I have seen much the same thing outside the rail ticket reservation office in Kolkata, and perhaps I should not make too much of it as an incident.

It was only a few short weeks later, however, that the insurgency began in earnest. For a long time there would be very few further visitors to the lovely Vale of Kashmir.

After a week, I returned to Delhi and then headed immediately to Agra, to see the Taj Mahal. I chartered a car and driver, because I wanted to also visit Fatehpur Sikri on the way.

Fatehpur Sikri was built by the emperor Akbar in the sixteenth century. His intention was to create a new capital city that honoured a Sufi Saint whose blessing the emperor believed had given him a male heir. This site was chosen, as it was close to the dwelling of the saint. Unfortunately, the area suffered from water shortages, and the city was abandoned shortly after the emperor died, after only 13 years occupation.

There remains the magnificent, well preserved, fortified city that I wanted to wander around for a few hours. Inside, there were a few stalls selling souvenirs and drinks, and a number of other visitors looking around, but generally there was an impression of peace and emptiness. I have not been back since, but I believe that it is now far more crowded, and that there are far more touts and hawkers on the site.

Performing bears at the side of the road. The cruel practice of dancing bears was made illegal in India in 1972, but was certainly still common in 1989. These ones were at the side of the road not far from Fatehpur Sikri, on my way to Agra.

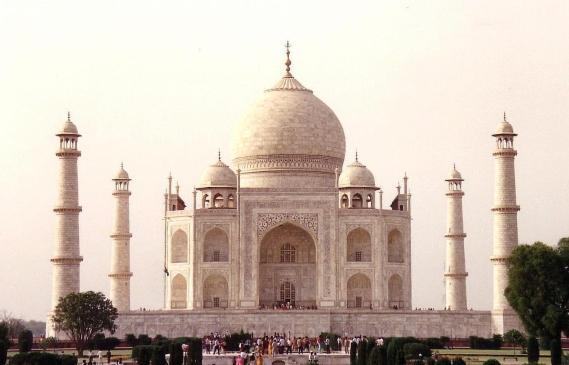

In Agra itself, I visited the Taj Mahal.

There are plenty of people who will tell you that it is over-hyped, and that there are many greater buildings in the world. It is possible, also, that some of these people have actually been to Agra.

It may be that there are some buildings that are more impressive, but how can you measure such things?

My first sight of it, as I walked through the gateway, made me catch my breath and stop still. For a moment, I could not believe how lovely it was. I then spent a long time wandering around the site, and I still think it one of the most beautiful and magnificent buildings that I have ever seen. I watched the afternoon light fade and die, and the sun go down, and the building seemed to glow and shimmer and almost float before me.

I left when they threw us all out at dusk, knowing that I had just seen something very special.