Well, they arrived yesterday.

I have finally got my family history book formatted and printed, and I reckon it looks quite decent. So all I need to do now is to get it posted out to family members.

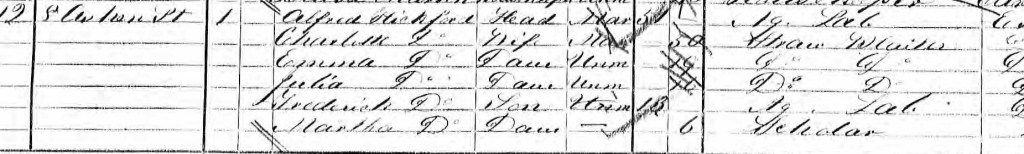

While researching all this, I naturally made a lot of discoveries. Some were certainly more unexpected than others, though. From previous research my father had done, we already suspected that my great grandfather had changed his name, possibly on a whim, from Prater to Canning. I was able to confirm this by, amongst other things, a comparison of various dates of birth in his family. This immediately removes the possibility of my searching back to see whether my name has any noble / famous / important roots. This is something that matters a lot to some people, although obviously only along the male line, which is why it seems to matter much more to men.

Although I turned it up too recently for the book, I have learned details about my father’s life in WWII which I would otherwise never have come to know. I had no idea – and seemingly nor had anyone else in the family – that from 1940 until joining the regular army in 1943 and being posted to India and Burma, he had been part of what had been dubbed ‘Churchill’s Secret Army’, soldiers trained to operate behind enemy lines in the event of a German invasion of Britain. Fulfilling the same role as the French Resistance, they would have carried out acts of sabotage and hit-and-run attacks to slow the enemy advance. it was only after that threat had receded that he joined the ‘Regulars’.

And then, less unexpectedly, there were the stories of extreme hardship: the early deaths, the poverty, the workhouse, tuberculosis and pleurisy…

Of course, if it was possible to search back far enough, we would all find we had a common early human ancestor, which gives the lie to the importance of race.

Does any of this research really matter? Well, in some ways, no. Does it sound crazy if I say that despite all my work, it does not matter that much to me? I’m very much in two minds over this. A lot of this felt more like an intellectual exercise than a personal quest. It was interesting to find out where my great grandparents and their parents had lived, for this felt just close enough to be a part of me. But before them? And especially when I could discover nothing more than their names and some vague dates? No, not really. Throughout this project I have been especially keen to be able to put names to old photographs, for this seemed the only way to make these people come alive again, or at least begin to. That I’ve been able to positively identify some of them feels more satisfying than pushing a line back another hundred years, although I do have nearly every branch back at least to the 1700’s, but in every case it is the stories I’ve found out about these people that matter.

But back to my question. Does any of this research matter? I do think it has the potential to bring us a little closer to our families by emphasising our shared history, and I’ve greatly enjoyed long discussions with cousins about our various researches and discoveries. But beyond that? Well, I’ve enjoyed learning the social history involved with my family, the realities of how people actually lived in the towns and countryside over the last few hundred years. And as well as emphasising my connection to my extended family it has also, as I wrote a few month ago, given me a greater sense of connection to the land where I live.

I have enjoyed exploring the past, but I’m not going to live there.