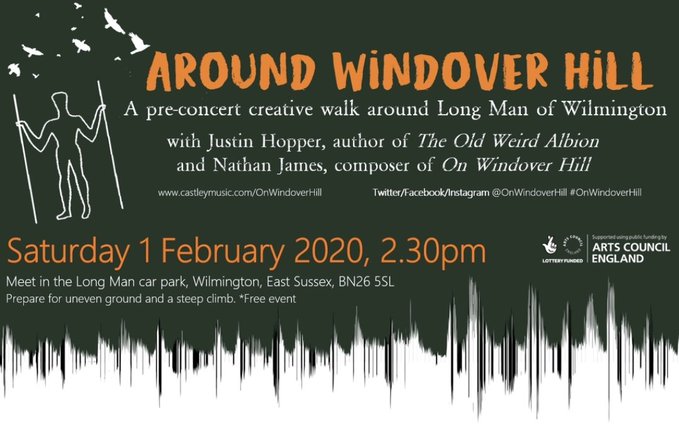

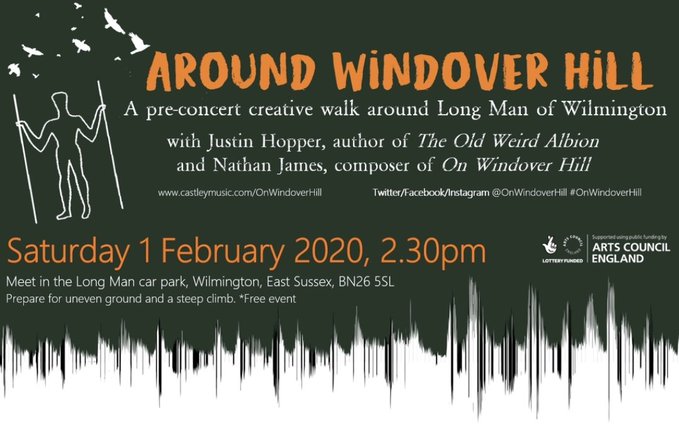

Yesterday, we joined a walk to the Long Man of Wilmington, on the South Downs in Sussex. The walk was led by composer Nathan James, and Justin Hopper, the author of The Old Weird Albion.

The Long Man is a chalk figure etched through the grass into the hillside, below the summit of Windover Hill, revealing the chalk that lies beneath. When and why it was first cut is the subject of myth and speculation – and that brings us neatly to Nathan’s new composition.

On 7th March, Nathan will premier his fantastic new choral work On Windover Hill at Boxgrove Priory, Chichester, Sussex. This has been inspired by the Long Man, its mythology, and the art that has arisen around it, as well as the written history and the geography of the surrounding land. It has a very English feel to it, in the tradition of Vaughan Williams or Holst.

Full details of the work and the performance can be found here. Tickets can also be bought by clicking ‘The Premier’ link in the sidebar there. We have ours, and it would be great to see it sold out!

This walk was by way of a taster for the concert, with a mixture of history and mythology imparted along the way, a poem from Peter Martin, read by himself, and extracts from stories read out by Justin, all of which referenced the Long Man. Also Anna Tabbush sang two folk songs, one of which was the only song known about the Long Man, appropriately enough called The Long Man and written by the late Maria Cunningham.

I’m not sure How many people I expected to see, but we were around forty, with a surprisingly large number being artists of one sort or another.

The weather was so much better than we had a right to expect – the forecast had been for clouds and rain, but the clouds cleared during the morning, and we had plenty of sunshine as we ascended, although it rather lived up to its name at the top, with more than enough wind for everyone.

Here, the remains of prehistoric burial mounds sit overlooking the Long Man, and the rest of the surrounding countryside.

Some landscapes seem to muck around with your perception of time, and Downland seems especially prone to this. I’m not entirely sure why this should be, but suspect it is a combination of factors.

It is a very open landscape, and other than the contours of the land and a few trees, frequently the only features that stand out are prehistoric ones, such as barrows and chalk figures. Due to the uncertainty around their origins, these have a timelessness about them, a fluidity when it comes to grasping their history. We see the long view, which perhaps works on our sense of time as well as space. The more recent additions to the landscape are usually in the form of fences, which can easily seem invisible as we look around for something less ephemeral than the open sky to fix our eyes on.

The Downs are an ancient landscape, in any case. When human beings recolonised what is now Britain after the last Ice Age, at first they kept to the higher ground which gave less impediment to travel and settlement than the marshy and thickly wooded lowlands. Most standing stones and burial mounds from the Neolithic or earlier are found on these higher areas.

I do not get these feelings in more recent landscapes. At a medieval castle or manor house, it is easy to imagine the inhabitants baking bread or sweeping corridors; activities as natural to us today as they were then. I feel a comfortable mixture of the old and the new, a recognisable timeline connecting the past with me.

But barrows, standing stones and hillside figures have a purpose alien and unknown to us. Step on the ground near these remains and you can feel the presence of the unknown. No wonder the belief in the past in faeries and elves who inhabited the underground, and who lived essentially out of time.

They offend our carefully erected sense of order and belonging and, perhaps, still pose a barely acknowledged threat to us today.

I might be imagining it, of course, but listening to the extracts from On Windover Hill on the website, I think I recognise that feeling in places, an unexpected musical response to my own feelings. And then Nathan’s description of his creative process on the website echoes some of this too.

I’m hooked!