It was Saturday 7th March, and we were in Chichester, Sussex, for the much-anticipated premier of Nathan James’ On Windover Hill cantata.

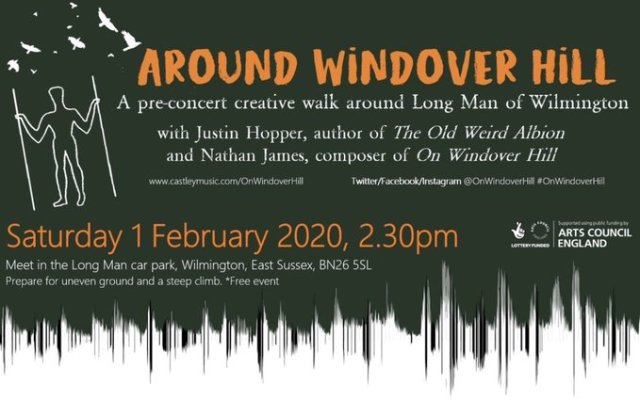

It took place in the church at Boxgrove Priory, in the village of the same name a few miles outside Chichester. Just over a month ago I posted here about a walk we joined at Windover Hill, viewing and discussing the Long Man of Wilmington – the subject of the cantata, which gives some of the background to this work.

Nathan describes this piece as ‘a result of 3 years of writing and research into the ancient figure and how it has inspired writers, poets, artists, and musicians’.

Nathan introducing the cantata

It was performed by the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Harlequin Chamber Choir, and Corra Sound, conducted by Amy Bebbington.

The cantata is in nine movements, with each movement scored around a piece from various times ranging from c 1340 BC to 1996. These diverse sources include English folk song, poetry, extracts from plays, literature, and even a piece from 14th century BC Egypt, used here because there is a carving on a chair found in the tomb of Tutankhamun which strongly resembles the Long Man.

The music has a very English feel to it, reminding me strongly at times of Vaughan Williams or Holst, another element that contributes to the sense of it being grounded in Sussex.

Much more about the music, and the story of the project, can be found on the On Windover Hill website, here.

Between several of the movements, there were readings chosen to help illustrate aspects of the mythology of the Long Man – poems, excerpts from books and an extract from an article arguing that the Long Man may have been, in fact, a Long Woman. All pieces by writers challenged by the meaning and significance of the figure. At the back of the church, too, there were a range of artworks inspired by the Long Man. And several times during the performance, a couple of dancers took the floor, their actions visually interpreting the subject of that particular movement.

This, what I might term holistic approach to staging the work, contributed strongly to the listeners total immersion in the work without, I think, distracting from it.

As well as the cantata, the program also consisted of several other pieces, all with a Sussex connection. It began with a beautiful piece by Thomas Weelkes (c 1576-1623) Hosanna to the Son of David. Weelkes, the program notes informed us, was frequently in trouble with the ecclesiastical authorities and was ‘noted and famed for a common drunkard and notorious swearer and blasphemer’. Strangely, I immediately felt an affinity to the fellow.

There were pieces, too, by Frank Bridge, John Ireland, an extract from Goblin Market by Ruth Gipps, and a piece largely unknown today: Wyndore (Windover) by Avril Coleridge-Taylor which was its first performance in this country for 82 years.

The acoustics in the church were wonderful, an especially appropriate setting for a choir. It was a hugely pleasurable and satisfying evening.

The Long Man, photographed on the pre-concert walk

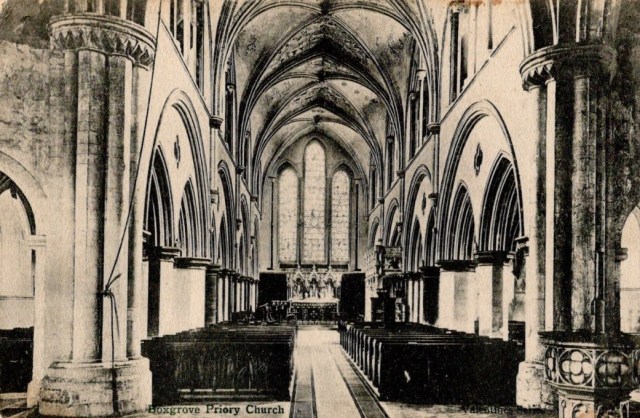

During the afternoon before the concert we wandered around Chichester for a while and I bought a few old postcards of Sussex from the indoor market including, by chance, this one of the Priory church, where the concert was held, about a hundred years ago.

It seemed to fit comfortably into the feeling of history, myth and tradition I felt that day.