I have been posting a bit about walking, recently, what with my frustration at being unable to do a great deal of it after my foot operation.

Foolishly, I made reference to the following episode in a reply to someone on one of the ‘walking’ posts, and admitted I might write about it sometime. Well, take this as a Warning From Someone Who Learned The Hard Way.

Thirty years ago I lived and worked in Oman. I was a seismologist, working on seismic data for an oil exploration company – but before you all shout at me, my conscience is clear. I don’t think I was particularly good at it, and I don’t think my efforts contributed to anyone finding any oil.

*phew!*

I do worry that as a result of this post, though, someone will now contact me and say ‘Hello, Mick. I was a geophysicist in Muscat when you were there, and I remember that one of the projects you worked on found absolutely stonking amounts of oil!’ But I doubt it.

Anyway, let me set the scene.

I lived near Muscat, the capital, which lies on the north coast of Oman. Behind me, towards the interior, ran a line of high hills

It is a massive simplification, but just at this point the hills run east to west, parallel with the coast, and consist of a series of ridges (jebels) and valleys (wadis). So to cross them from north to south (or in the opposite direction) the traveller has to continually climb up and down for the entire journey.

I bet you can already see where this is going.

When I had a few free hours, I would often walk out of my house, and up into the hills to just wander around and explore. As a result of this, I knew the first couple of wadis and jebels pretty well. There was a high, prominent jebel to the south, though, which was the final ridge before the land fell away to a wide stony plain, and I had never gone that far on foot up till then. This ridge was easy to spot, however, as there was a large microwave (radio) transmitter on top, and I knew it was the final ridge as we would often drive past it on the south side.

I had a day off.

I don’t know exactly what time of year it was, but it must have been in the ‘cooler’ season, because even I wouldn’t have been stupid enough to try when it was really hot.

Surely?

I didn’t even have a proper rucksack, I had a small roll-bag, which I slung uncomfortably over my shoulder. Inside, I had a single bottle of water, and a dozen small packaged juice drinks. I had a compass, but no map. I had a hat, I had a camera.

So, well-equipped and well-prepared, I set off.

The first couple of hours went well. I crossed two or three ridges and felt fine. I guess I should say at this point, that I was pretty fit. The project probably wasn’t an unreasonable one, by any means.

Certainly not for someone with the right equipment and supplies.

I was probably just beginning to feel a bit hot and tired when I crested what I thought would be the penultimate ridge, only to find I was looking down on another two smaller ridges that I still had to cross before reaching the final large one.

And the large one was looking very large indeed!

I can be ridiculously, unreasonably, stubborn, at times. I remember that on the final ascent I had to force my legs to bend and stretch, to take each step, but the top was getting nearer and nearer and I wasn’t going to give in.

I made it.

I enjoyed the view and the moment. It was, admittedly, very impressive and I knew I’d done pretty well to get there.

And really, all I needed to do then was to carry on down the south side of the ridge, walk another kilometre or two to the road I mentioned earlier, and hitch a lift back to Muscat.

Have I mentioned I can be unreasonably stubborn?

I turned around and started heading down the north side towards home.

I could draw this out into a long dramatic story of my walk, but I’ll give you the abbreviated version.

I found I was in difficulty as soon as I had to go up the next hill. especially as I had finished all my drinks by then.

It took me several hours and more energy than I realised I had at one point, just to get to the final ridge. But at that point, I knew I no longer had the energy or strength for that last climb. I could not do it. Fortunately for me, I knew I could follow the valley for a mile or two east, where it would come out to the coast plain. So I turned and stumbled that way. By now, I was desperate to find some sort of shade, just for a moment, but there was nothing.

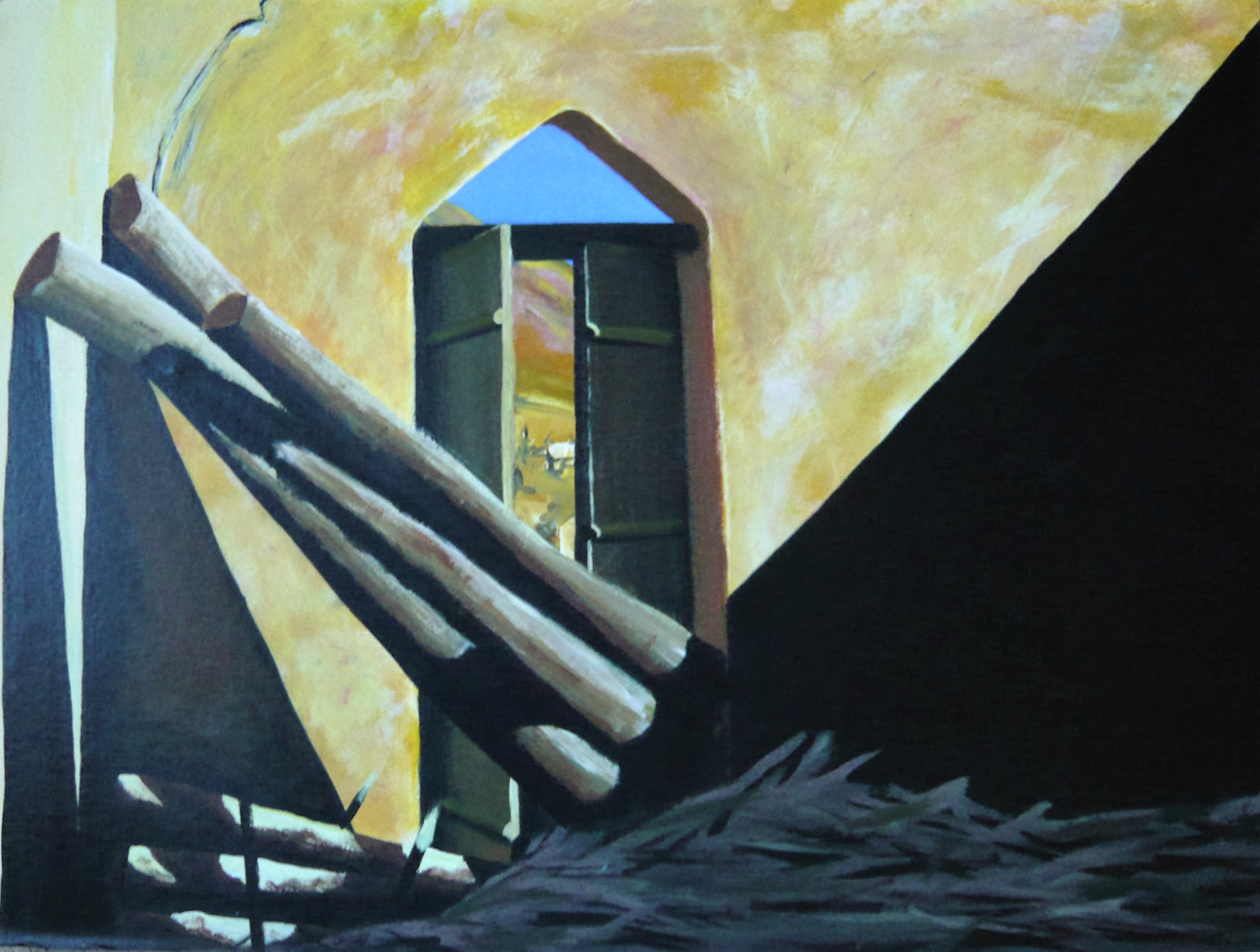

But I staggered along, and as the hills either side dropped down, I came to a cluster of buildings. I don’t know what exactly they were, but I staggered in through a doorway and an Indian working there took one look at me, sat me down and brought me water.

‘Slowly!’ I remember him saying, as I poured it down my throat. ‘Not good to drink too quick!’

I didn’t care. I drank it like a camel on steroids given twenty seconds to fill up. I got through an awful lot of water, but he made me sit and rest for a while before I went off again. I think he offered me food, which I refused, and I think he offered to find someone to drive me, but I don’t really remember too much from that point on. I did walk home eventually, though. I just hope I thanked him sufficiently.

It was not one of my more intelligent adventures.